Nothing says that an art piece managed to pass the test of time like the fact that, even more than 60 years later, that piece is still talked about and regularly appears in various lists of the most influential works in cinema. This is precisely the case with Masaki Kobayashi‘s Kwaidan, which remains an Oscar-nominated, undisputed staple in more than one genre tradition, despite having been released in 1964. The film is the ultimate example of the supernatural subgenre, as even its title aptly suggests: “kwaidan” is an archaic version of the word “kaidan,” literally meaning “ghost story.” In Kobayashi’s film, we actually get four of those, since it is also one of the notable examples of an anthology horror film, which already existed at the time, but didn’t appear all that often. Lastly, Kobayashi’s feature is a formative piece for the J-horror tradition, one that has demonstrated some of the crucial (and delightfully chilling) aesthetic choices that we will come to know and love in modern Japanese horror movies, such as Ringu and Ju-on.

‘Kwaidan’ Throws Us into a Reality Where the Supernatural Always Lurks Around the Corner

Despite the presence of the narrating voice-over, the four novellas in Kwaidan aren’t connected in any way, other than the fact that all of them feature characters who encounter supernatural forces. In the first story, a swordsman leaves his wife for another woman as a way to climb the social ladder; several years later, deeply regretting his choices, he goes back to his true love — with unnerving results. In the second one, arguably, the best known from the film, a young wood-cutter encounters a yuki-onna (a female snow spirit who often appears in Japanese folk tales), and has to promise not to ever tell anyone about it or face untimely death. The third novella is centered around a bling musician, Hoichi, who unwittingly starts performing in front of the ghosts of the Emperor and his samurai. The film then concludes with a story about a writer who recounts an old legend and might get drawn into it, quite literally.

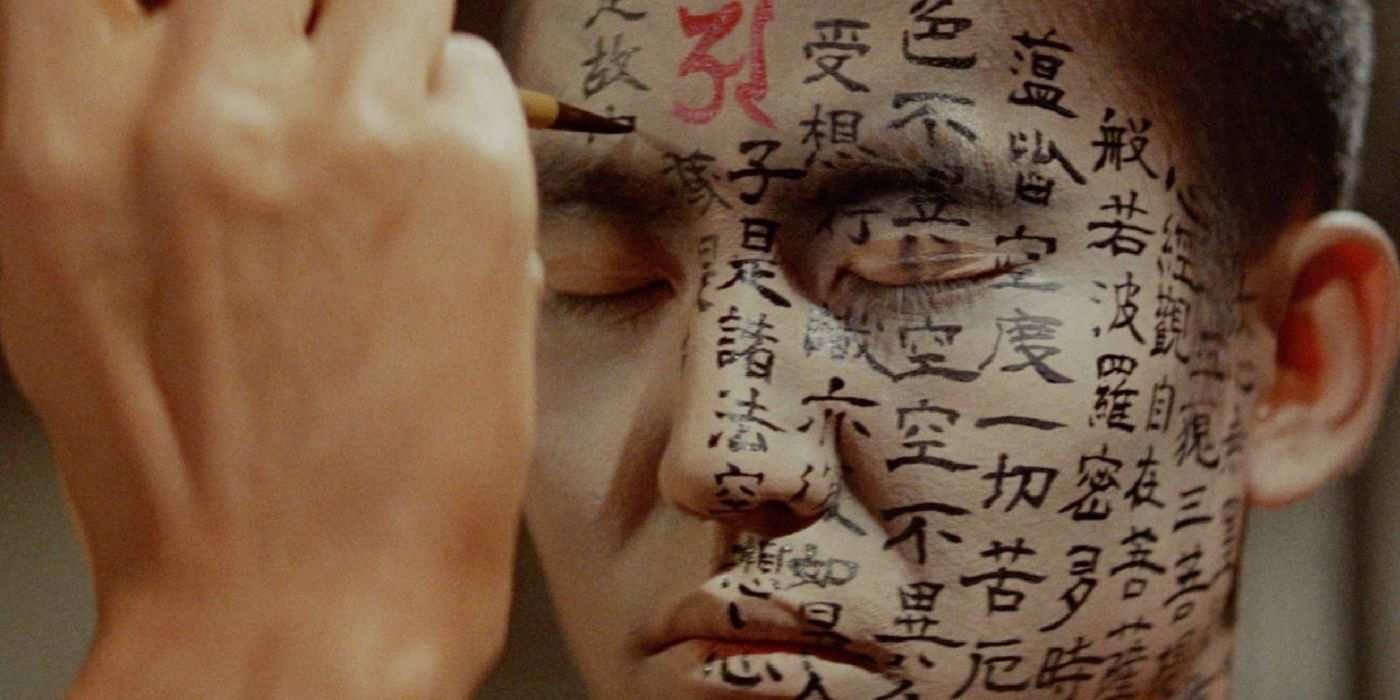

Like multiple Japanese genre films that would follow, Kwaidan and the four stories told in it have deep roots in national folklore and are based on the book of dark tales by Lufcadio Hearn. Unsurprisingly, Kobayashi makes use of the imagery suggested by the old legends: a female ghost dressed in white, the snowy landscapes, the long black hair, which seems to have a hostile mind of its own (and would go on to become a trademark of so many vengeful ghosts, such as Sadako and Kayako). At the same time, the director, who previously studied philosophy and East Asian art, also comes up with his own stylistic tools, such as finding a way to show the appearances of ghosts and other supernatural elements in a way that would be frightening, but also seamless. This is another crucial aspect of the Japanese folklore tradition: the paranormal is usually a part of the familiar reality, just waiting to burst through the facade.

Ghost Stories in ‘Kwaidan’ Are as Beautiful as They Are Chilling

Therein lies a crucial difference from the Western cinematic tradition of horror, despite Japan going through a phase of being largely influenced by American culture at that time. Unlike western ghost stories, most of which tend to rely on sudden, unpredictable scares or vivid imagery, Kwaidan and its spiritual follow-ups appeal to the audience’s emotions first and foremost, effectively crawling under our collective skin. Instead of outright showing something we should objectively be scared of, Kobayashi prefers to wait, teasing, hinting, and foreshadowing. The sense of fear and foreboding in every story is eventually born out of a gradually built, slowly increasing tension, an uneasy anticipation of something terrible inevitably happening, since such is the nature of this world.

The horror of Kobayashi’s film is also rooted in its astounding beauty. Roger Ebert, in his review of another major Kobayashi’s work, Harakiri, famously noted that Kwaidan is one of the most beautiful movies he has seen, which is definitely saying something. Unlike many other great movies with fantasy or horror elements of that period, such as Kenji Mizoguchi‘s Ugetsu or Kaneto Shindô‘s Onibaba, Kwaidan isn’t black and white, and makes artistic and meaningful use of color and its symbolism, which the modern tradition of J-horror will also actively engage. Every novella is painted in its own dominant color, with glimpses of red finding its way into all of them. Kobayashi dives into an expressionist visual style, building his own world on screen, consisting of elaborately created set pieces for most of the exterior scenes, such as the landscape with a giant eye or the mysterious graveyard.

As the film’s visual aesthetics and the ever-present musical score create an impression of being inside a dark fairy tale or a horror epic, the remnants of reality and familiar human behavior still linger. Kobayashi has always been fascinated with the motives of human imperfection, corruption, and moral compromise (especially after his own experience during the war), which he previously explored in his opus magnum, The Human Condition. The form of a kaidan also proves to be effective in digging into these themes, as the folk tales the film is based on inevitably feature a morality play, with various characters being challenged and tested by life, death, and spirits. Despite the differences in the plots, the common thread here becomes the importance of people taking responsibility for their deeds, words, and the art they come up with. What additionally makes Kwaidan so hauntingly effective even after all these years is that, at the very end, the film challenges the viewers to become responsible too, for assigning the final meaning to this beautiful, macabre tale.

Kwaidan is available to stream on HBO Max in the U.S.

- Release Date

-

December 29, 1964

- Runtime

-

183 Minutes

- Director

-

Masaki Kobayashi

- Writers

-

Yôko Mizuki, Lafcadio Hearn

-

-

Michiyo Aratama

First Wife

-

Misako Watanabe

Second Wife

-