Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

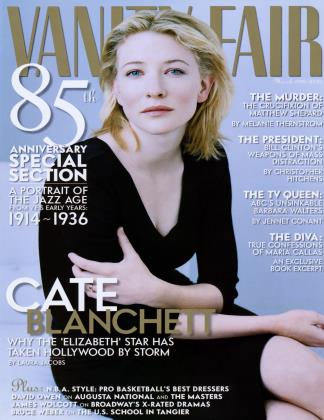

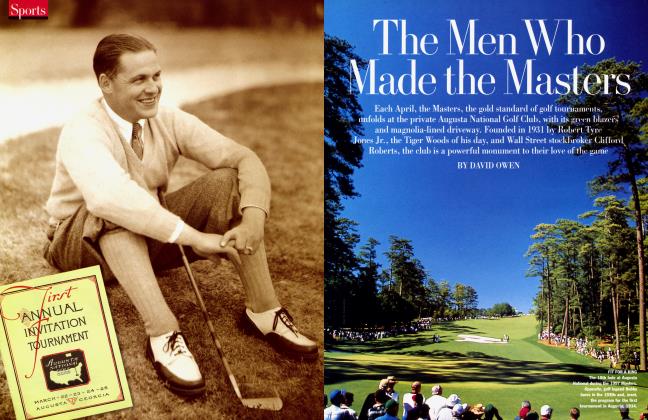

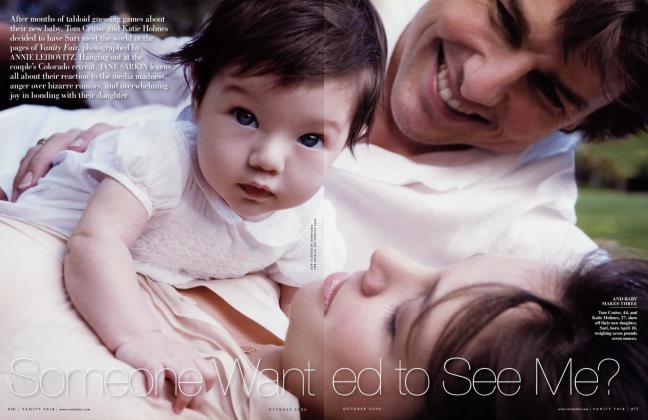

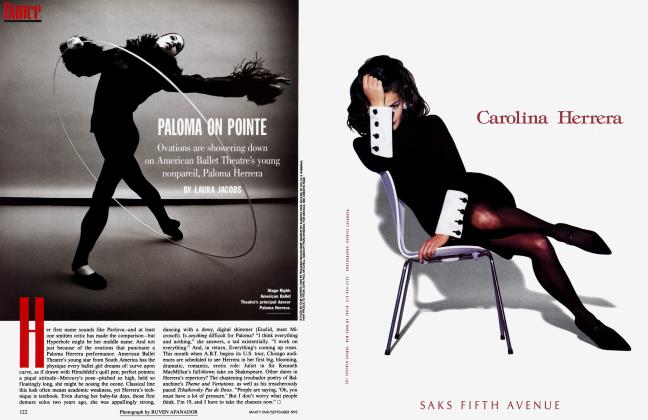

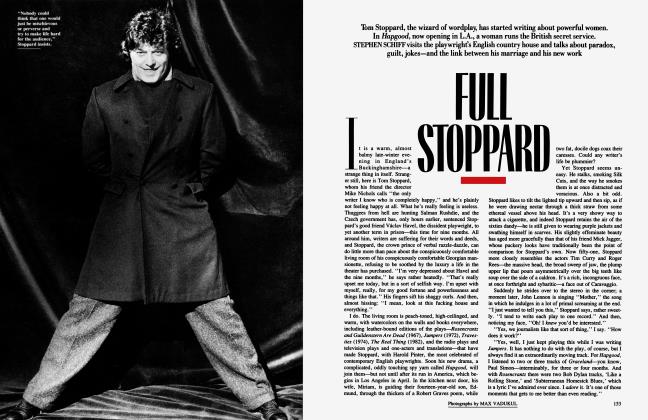

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCate Blanchett shone for most of this decade on the Sydney stage, putting her stamp on such plum roles as Miranda, Ophelia, and Electra, and lit up the screen opposite Ralph Fiennes in Oscar and Lucinda. But it was the 29-year-old Australian's Golden Globe Award—winning performance in Elizabeth that confirmed her destiny. As Blanchett lends her now-you-see-it-now-you-don't incandescence to Pushing Tin, with John Cusack, The Talented Mr. Ripley, directed by Anthony Minghella, and Oscar Wilde's An Ideal Husband, she talks to LAURA JACOBS about her real hair color, her Big Break, and the off-the-record subject of her husband, Andrew Upton

March 1999 Laura JacobsCate Blanchett shone for most of this decade on the Sydney stage, putting her stamp on such plum roles as Miranda, Ophelia, and Electra, and lit up the screen opposite Ralph Fiennes in Oscar and Lucinda. But it was the 29-year-old Australian's Golden Globe Award—winning performance in Elizabeth that confirmed her destiny. As Blanchett lends her now-you-see-it-now-you-don't incandescence to Pushing Tin, with John Cusack, The Talented Mr. Ripley, directed by Anthony Minghella, and Oscar Wilde's An Ideal Husband, she talks to LAURA JACOBS about her real hair color, her Big Break, and the off-the-record subject of her husband, Andrew Upton

March 1999 Laura Jacobs

Cate Blanchett thinks it's "luck." She believes she's been in the right places at the right times, and that's why she is winning one bold role after another. In discussing her career so far, Blanchett uses the word "fortunate" again and again—as if the Fates, for some inexplicable reason, have taken a shine to her. But it is she who shines, she who is coming on like a strange force of nature. Cate Blanchett is the actress from Australia who has stolen the thunder from a host of American ingenues. A distant rumble in 1997's Paradise Road, a summer storm later that year in Oscar and Lucinda, Blanchett is heat lightning in 1998's Elizabeth, the slim frame and white fuse at the center of Shekhar Kapur's whirling, brooding historical fantasia. "When I first saw Cate," remembers Kapur, "I could see in her face that she had a great destiny as an actress." She would stand up to all those dark towers.

The face is fascinating. It's so new and still so little written about that there's no cliche description as yet, though the labels "luminous" and "translucent" are flying fast. With that breadth across the cheekbones, a correspondingly wide and sunny smile, and a pouty chin, she can look like Pippi Longstocking all grown up. In profile, no smile, you see the drawn-down corner of the mouth echoed in the delicate, drawn-down nostril—she's like Leonardo's archangel, invincible and severe.

"There's a duality in Cate," says actor, friend, and fellow Australian Geoffrey Rush, who plays Sir Francis Walsingham, Master of Spies, in Elizabeth. "She's got a very cheeky sense of humor, a very galumphing kind of down-to-earth personality. And then suddenly you look at her and go, 'My God, you're so strikingly beautiful.' She seems to flicker between the two."

That flicker's the thing—it captivates directors. Gillian Armstrong saw it first when she was casting Oscar and Lucinda. "There are many wonderful actresses and many really beautiful actresses," says Armstrong, "but I always felt Lucinda couldn't be just beautiful, she had to have a little something that was off. When I saw Cate's auditions, the thing I realized she had—and I hadn't even articulated that we were looking for—was this ability to go into other worlds.... Cate has a slightly magical quality. There's something extraordinary about her."

Five long months into his search for an actress to play Elizabeth, Kapur saw it, too, quite by chance, when he was watching a promo reel of Oscar and Lucinda—the swimming scene, when Blanchett's pale face bubbles up to the water's surface. "You're looking for a face," says Kapur. "It's very difficult to describe what you are looking for until you see it. In that shot, there was a certain ethereal quality. I was totally fascinated because that's how I saw Elizabeth at the end, very ethereal. And there was a certain fire in her eyes."

Kapur could have saved himself five months if he had taken seriously the advice of his casting director, Vanessa Pereira: she had wanted him to go to Sydney to see a particular young woman onstage. Having already traveled from India to England to do the casting, he assumed she was just joking. When he later discovered Blanchett in the bubbles, "I was so shocked that I called my casting director up and said, 'Why have you not told me about this girl?' And she said, 'Well, who do you think I was asking you to go to Sydney and see onstage?' " The fact is, Blanchett has been hot stuff on the Sydney stage since 1992, when she graduated from Australia's National Institute of Dramatic Art and began building an impressive resume of plum roles: Miranda in The Tempest, Ophelia in Hamlet, Nina in The Seagull. Blessedly—or, again, luckily—Blanchett is not emerging as a teenager pretending to be an actress. Her step to the silver screen is not silver-spoon. At 29, having just won a Golden Globe best-actress award for Elizabeth, and with an Oscar nomination in the air, Cate is ready for her close-up.

'No," she says when I ask if she grew up wanting to be an actress. "I think any child that is not comatose and shows off a little bit, people say that she's bound to be an actor. I was much more bossy than that, and by the age of seven I thought, I'll direct—though I don't know enough to direct traffic yet." Blanchett up close does not seem bossy, but thoughtful and somewhat inward. She has deep-set slate-blue eyes and a dusting of freckles so fine that you later wonder if you didn't imagine them. Though she's been various shades of redhead in her movies, in real life Blanchett is blonde, "as much as anyone," she says, smiling, "can ever be called a natural blonde."

Blanchett was born and raised in Melbourne. She was a child who liked school and studying—"I was a perfectionist"—but also remembers being a loner. At high school, "an enormous school, about 2,000 girls," she acted in plays and was on the tennis team. Her nickname was Blanche. When the subject turns to her family, she very carefully apologizes. "I'm happy to talk about my life, but I feel bad for my family, talking about them, because they're all quite private people."

This is what she will say: "My father was American. He was in the navy, met my mum, who was a teacher in Melbourne. He was in advertising, and then they went into business together. And he passed away when I was 10.... Oh, look, it's a long time ago," she says, reassuringly. "I feel worse for my mother than I do for me. I think kids are quite resilient."

A few more facts are pried out. She's the middle child—"the peacemaker"—between an older brother, Bob, who is in computers, and a younger sister; Genevieve, a theater designer in Sydney ("We're hoping one day to work together"). Oh, and they had a dog named Snoopy, who was "very low and very squat and very fast."

Blanchett's story picks up momentum in college, at Melbourne University, where she was studying economics and fine arts. "I really wanted to get to international relations, which was in fourth year, so I guess you could say it was sort of restlessness that led me to acting, because I just couldn't stand sitting through four years of the cattle runs in 1860."

"When I first saw Cate," says director Shekhar Kapur, "I could see in her face that she had a great destiny as an actress."

And it was her acting in a university production of the Sarah Daniels play Byrthrite that led a fellow, not-particularly-friendly coed to wonder, "Why haven't you thought about going to drama school?"

"This girl in the play," recalls Blanchett, "frankly told me that she didn't like me. Not with any malice. She just said some people you don't get on with and some people you do. And I was stunned by her honesty. I thought, There are people in the world who don't like me? What an idiot I was. Well, she suggested I go, and I thought, I'll give it a go. I went to the audition and I got in."

Blanchett left university and entered the National Institute of Dramatic Art, but she wasn't committed to becoming an actress. "I still thought I'd go back and do architecture or something."

Then came what is always called the Big Break. It happened during Blanchett's third year at drama school, and in her case it was not easy, not only because it involved the monumental title role of Electra, but also because it came at someone else's expense.

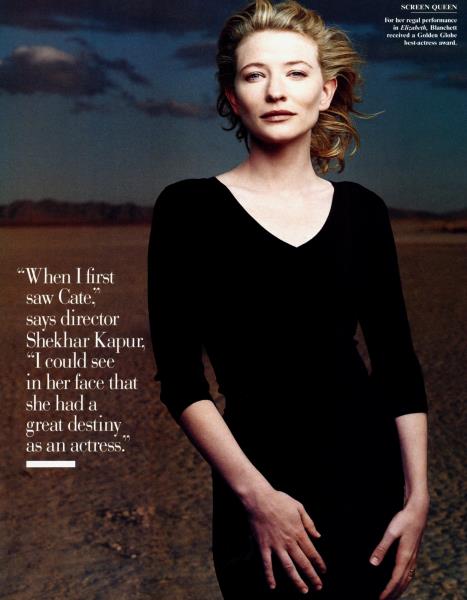

SCREEN QUEEN for her regal performance in Elizabeth, Blanchett received a Golden Globe best-actress award.

SCREEN QUEEN for her regal performance in Elizabeth, Blanchett received a Golden Globe best-actress award.

'It was pretty awful, pretty chaotic. . . . It was this messy situation where another girl was supposed to play it— I still feel bad about it—and I ended up playing it. I didn't have long to rehearse, because the cast change happened, and I was the one who was available to be there over the week and a half, so . . .

"You know what drama school is like," she continues. "It was one of those situations where, because I had to assume the role, I didn't realize how much ill feeling there was till afterwards. For me there was no time to fear. You're focusing completely on something, and it doesn't matter whether it succeeds or fails—and that, in fact, is out of your hands."

Geoffrey Rush well remembers that Electra, a modem version of the Greek classic, because at the time he was sharing a house with Lindy Davies, the woman who was directing the play. "She would come home and say, 'There is this astonishing young woman working on this production.' ... There was already a buzz around Cate."

And her Electra? "Amazing," says Rush. "The assurance. You're seeing somebody who's already, even in drama school, having a kind of consummate facility to actually be able to do it. Not only to bring great imaginative resources to it, but to define it with such emotional clarity and to etch it with such classical dimensions."

I remind Rush of how Blanchett was thrown in at the last minute. "I think that's a great indicator of Cate. I mean, the challenge of Elizabeth was enormous—being an outsider to British culture. In some ways that ups the stakes a bit. Cate's got the kind of resilience and resources to match that challenge. I think that's what happened with Electra."

Within six months of graduating from drama school, Blanchett landed across from Rush in the Sydney Theatre Company production of Oleanna, David Mamet's controversial meditation on gender politics. It was another event in Sydney theater—huge hit, sold out, season extended. For Blanchett, it was another breakthrough. "I thought, I can't do this play, it's a misogynist piece of crap. But it angered me so much that I had to do it. I wrestled with it; I was so internal the whole time. Then, when we had the dress rehearsal in front of the theater staff, when Geoffrey went to hit me at the end, I laughed—I was outside the scene—and Michael Gow, the director, said, 'If you do that onstage on opening night I will sack you,' and I just wept and wept."

Then Gow gave her the magic key. "He said, 'Now do it again and don't take your eyes off Geoffrey.

"Cate's a world-class champion," says Gillian Armstrong. "She has the intelligence and the craft to choose carefully."

Don't think about the words you're going to say, just look at him and listen.' The little bit of energy I had left was focused out on Geoffrey. The play took off. Because I was no longer thinking about myself." Watch Blanchett in Paradise Road, Oscar and Lucinda, or Elizabeth and you'll see her doing something rare in movies today: you'll see her listening.

When she does speak, there's that remarkable voice, silky on the surface but drawn downward as well, primed for her sudden dives into a rich, dark lower register. Blanchett is fluent when talking about the nuts and bolts of acting, never once drifting into ditsy actorspeak about "getting centered," but she is absolutely delighted analyzing the arts beyond the set. She bemoans the fact that she hasn't gotten through Proust yet, and is full of admiration for the Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert, whose poems she's been reading while in New York for the premiere of Elizabeth. Her favorite play of Shakespeare's is Hamlet: "I love what it wrestles with. A lot of productions fail because they try to stamp a decision on the play rather than letting the complexities breathe." She adores dance, particularly the Tanztheater Wuppertal of Pina Bausch and the pyrotechnics of Britain's DV8 Physical Theatre. "Good choreography deals with moments of suspension, and I think good acting does, too. Watch someone gathering themselves before they go into action."

Her favorite subject, however, is one she has put off-limits. And yet Blanchett can't help mentioning, like light breaking into the conversation, her husband, the Australian screenwriter Andrew Upton, whose film-editing credits include Babe: Pig in the City. "He's one of the few grounded people I know whose head is in the stars. He's able to stretch between the sky and the earth. Those people are very rare."

They met in 1997 while she was performing Chekhov—Nina in The Seagull— and they didn't like each other at first. "He thought I was aloof and I thought he was arrogant. And it just shows how wrong you can be. But once he kissed me, that was that."

And did life influence art? "Every night I would come to the theater so happy, so fulfilled, and I thought, How am I going to get to the last scene, where my life has to be destroyed? I thought, O.K., if I can't cry I'll just apologize to everyone afterwards. But because the play was so good, and because joy and grief actually come from the same wellspring, I was just carried along."

Blanchett and Upton live in an apartment near the water in Sydney. "We will eventually—it's part of the Australian dream—have our own house, in Sydney," says Blanchett. Eventually, children too. "One hopes. It's one of the few miracles left to us, really."

The couple tries hard not to be separated by Blanchett's location work. Elizabeth, for instance, shot in London and the North of England, meant three months of longdistance calls. "He was working in Australia and I was doing Elizabeth and it was so painful_We just couldn't do it again. So Andrew's been flexible this year with his work [a screenplay]. He's been able to take it with him. We've been away from home for about eight months. But we've been together."

"I admire Andrew," says Kapur. "I have rarely seen a man that is so supportive of his wife's success. Cate is one of the luckiest girls in the world to have a husband like Andrew. That one person can see her through what are going to be turbulent times for her ... You know, success is the Devil. You have to be able to keep that Devil at bay."

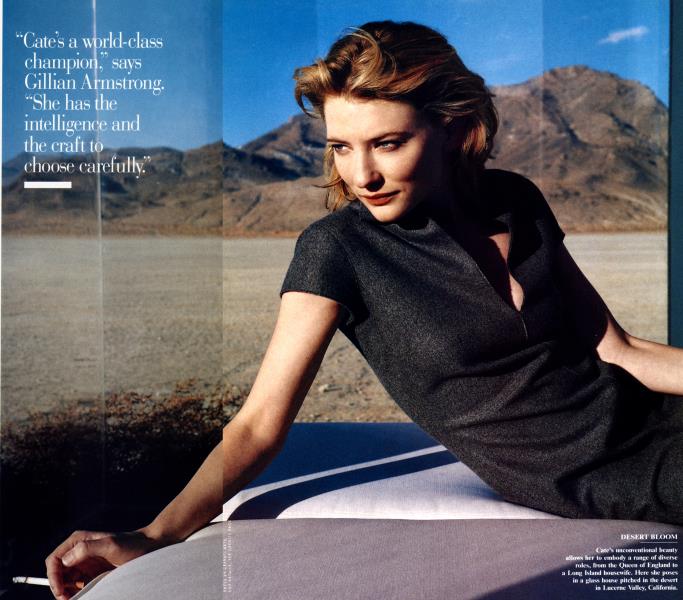

DESERT BLOOM Cate's unconventional beauty allows her to embody a range of diverse roles, from the Queen of England to a Long Island housewife. Here she poses in a glass house pitched in the desert in Lucerne Valley, California.

DESERT BLOOM Cate's unconventional beauty allows her to embody a range of diverse roles, from the Queen of England to a Long Island housewife. Here she poses in a glass house pitched in the desert in Lucerne Valley, California.

'Glass is a thing in disguise, an actor, is not solid at all, but a liquid_While it is as frail as the ice on a Parramatta puddle, it is stronger under compression than Sydney sandstone." These are lines from Peter Carey's novel Oscar and Lucinda, lines describing Lucinda's fascination with glass. They might describe Cate Blanchett as well, how she is both crystalline and mercurial, how in an instant her beauty, her shimmer, may simply drop out, leaving only cold clarity.

"Go on," she laughs, "say it. I've looked ugly. That's O.K. The greatest compliment I think I've ever had was when another actor said that I had 'an actor's face.' There's a line in the Botho Strauss play Big and Little where it describes a character as 'a woman ... not old, not young,' and I hope that I'm a woman, not ugly, not beautiful. I'm as vain as the next person, let's face it, but it's really important to try to shed that vanity. I'm not opposed to looking what is commonly termed as ugly."

"It's a strange thing about her," muses Kapur. "There are times when she can look fascinating and unattractive. But that actually speaks of a great actor. The structure is not changing; what's happening is the mind is taking over the face. The mind is taking over the body and expressing itself through the face and through the eyes. That's what is remarkable about Cate. Whatever is happening in her mind you can see on her features.

"And Cate is capable of minute changes," he continues. "She's capable of retaining a whole performance in a shot and in a scene, and tweaking something that you think could be tweaked—2 percent, 1 percent. She's extremely finely tuned. And that is rare."

"She's a world-class champion," says Gillian Armstrong. "She has the intelligence and the craft to choose carefully. And she's brave—she'll always push herself. And she's adorable as well, such fun to work with."

Blanchett has already chosen her next roles. "An actor puts their cards on the table by what they do," says Geoffrey Rush, "and the first thing Cate did after Elizabeth was get a really interesting role in an ensemble—and not carry a picture. That's a film called Pushing Tin, with John Cusack." Directed by Mike Newell, Pushing Tin is a black comedy about air-traffic controllers, and it has Blanchett playing a Long Island housewife.

She has also finished filming Oscar Wilde's An Ideal Husband— directed by Oliver Parker and co-starring Rupert Everett and Minnie Driver—and The Talented Mr: Ripley, a psychological thriller based on Patricia Highsmith's novel, directed by Anthony Minghella and co-starring Matt Damon, Gwyneth Paltrow, and Jude Law. For those eager to see Blanchett in person, on the stage, she will open in London this April, in a role she was born to play: Susan Traherne in David Hare's Plenty.

"If I had my way," says Blanchett, considering her position in the world at this moment, "if I was lucky enough, if I could be on the brink my entire life—that great sense of expectation and excitement without the disappointment—that would be a perfect state."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now